Growing up, Nicholas Buccola was an inquisitive kid. It wasn’t just politics and the webs spun from political debates that gripped Buccola at such an early age, but the human faces behind each story. “I was always interested in questions of justice,” Buccola remembers.

The more Buccola reflected on the vexing nature of justice, the more certain he was that political thought would play an outsized role in his career. And indeed, it did. Buccola is now an IHS Senior Fellow and Elizabeth and Morris Glicksman Chair in political science at Linfield University, where he regularly engages with bright students about the minds and ideas that forged the liberation movement.

As a Summer Graduate Research Fellow, Buccola was just finishing up his dissertation. At the program, he presented his chapter on Frederick Douglass’ theory of self-ownership. Another participant in the fellowship was Brandon Turner, whose formative, yet entertaining grip on ideas struck Buccola as deeply insightful.

“Brandon is the kind of guy whom everyone gravitates toward to learn more and engage in new concepts,” says Buccola cheerfully. Both maintain a strong friendship that sprang from when they were first roommates during their time at the IHS fellowship. In fact, each has invited the other to speak on their respective campuses, a collaboration Buccola is thankful to continue.

“I think of what IHS does as a natural partnership. The opportunity to sit down with an idea, so to speak, is what learning is all about. My personal mission is to bring students, faculty, and staff members of the community together to have serious conversations about ideas that matter. I’ve had a lot of interesting and invigorating experiences this way with the support of IHS.”

– Nicholas Buccola

In 2012, Buccola assigned a name to these regular convenings: The Frederick Douglass Forum on law, rights and justice, which is celebrating its tenth anniversary this year. These discussions give students the chance to immerse themselves in the hotly contested debates that have shaped the course of history. Students explore the writings of Frederick Douglass and other men and women who fought for freedom, plunging their minds into the turbulent times that defined the abolitionist struggle.

Every IHS partnership, notes Buccola, leads to memorable takeaways given the diverse and interdisciplinary nature of the programs. In one case, Buccola was struck by the ease with which one psychology student located a key point Douglass had made in his exposition of plantation life. He says that “each IHS seminar creates a space for participants to engage with material they otherwise might not engage with, and to do it in the company of people coming from multiple perspectives and disciplinary backgrounds.”

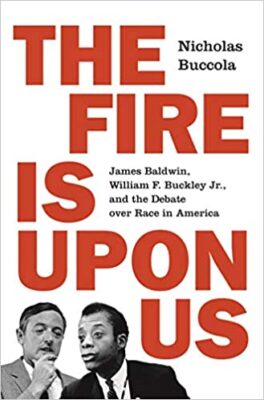

In his most recent book, “The Fire Is Upon Us” (2019), Buccola examines the 1965 Cambridge Union debate between James Baldwin and William F. Buckley Jr. Both had starkly different upbringings — Buckley was raised in affluence, Baldwin in poverty — and their ideas would turn out to be just as divergent as their backgrounds. Then in 1965, both intellectuals got the opportunity to clash with another on center stage, culminating in a debate that encapsulated two polar worldviews.

“The magic of the debate is that it illuminated this abiding gulf in two thinkers whose ideas helped spawn two movements. One the one hand, you had this towering figure in Buckley who led the modern conservative movement. On the other, you have Baldwin, who Malcolm X aptly called the poet of the civil rights revolution.”

– Nicholas Buccola

That night, Baldwin argued in favor of the motion, in which he offered his reasons why the American dream is at the expense of African Americans. It was Baldwin’s ability to venture inside the minds of those most affected by racial discrimination — including white perpetrators — that prepared him well for the searing speech he was about to give before a crowd of hundreds in the famous Debate Chamber at Cambridge Union.

But Baldwin also posed a weighty dilemma before the audience: How can African Americans gain membership into the American success story if they themselves are not fully accepted as equals? It was the “system of reality” that needs to be seriously inspected, Baldwin argued, if ever the racial question was to be put to rest.

Buckley countered by defending the American ideals and the opportunities that African Americans were now afforded. He remarked that a certain danger lurked around the corner if personal responsibility was deflected and opportunities unseized. He continued by noting that the “engines of concern” are in fact working, and in the attempt to solve racial discrimination, one must not abandon the pistons that drive what he considers to be genuine progress.

Buccola stresses how both figures were able to peel back the layers that characterized the mounting racial reckoning that was still taking shape. The oratory flare combined with personal reflections on race stirred the audience and captured the tense divisions that defined the political moment.

Buccola says that the question of freedom, and how it’s interpreted, is the central theme that ties his work together. Moreover, the idea of freedom is often left hollow when the practical elements are ignored. These two pieces comprise Buccola’s research focus.

“The conception of freedom — and the economic, social, and political institutions that bring it about — are major pillars to my research. How can it be that seemingly opposite camps tout very similar language to support their positions? This paradox has always fascinated me.”

– Nicholas Buccola

Buccola ends by saying that progress lies in our willingness to engage and dwell in the spaces where we disagree the most. “The commitment that IHS has taken to organize these forms of discussions is essential if we are to find wisdom in difficult conversations,” he says. Buccola’s work similarly seeks to engage the conversations that have shaped and will continue to shape our views on complicated issues.

True intellectual advancement is made on stages like the one at Cambridge Union. Buccola understands that we shouldn’t shy away from having those discussions, since they provide a lasting lens through which to see the world and what we ought to do to improve it.