The past two-and-a-half centuries have witnessed extraordinary improvement in the human condition. More people today than in the long stretch of human history have freedom and opportunity to live their fullest lives. This transformation has been possible because of the advance of Enlightenment-era liberalism—the philosophical, moral, political, and economic system that begins with a default respect for every person.

From this starting point follow other liberal principles, such as individual liberty, constitutionally constrained government, equal rights, equality before the law, and intellectual openness.

And it’s these principles that underlie the good society, a tolerant and pluralistic society in which individuals and communities thrive in a context of peaceful cooperation, intellectual progress, and economic prosperity.

It must be acknowledged that liberalism in practice has never fully lived up to its ideals. That said, it’s those ideals that have guided us toward greater freedom, equality, and human flourishing over time.

And it’s for that reason that we should be concerned that illiberalism is on the rise—globally and here at home and on both the left and right ideological extremes. Even within mainstream discourse, liberalism’s openness to the world, to ideas, and to the whirling dance of economic and cultural change has led some prominent scholars and public intellectuals to declare liberalism a failed project.

There have been times when people of ideas have focused intensely on the liberal project—in its origins and when it has been under threat. And times when, feeling confident that liberalism was the water in which we safely swam, they understandably focused on other priorities. Whether it’s the illiberalism we’re seeing in contemporary politics, or on campus, or the January 6th crowd, we’re in a moment when we need to make the liberal project, once again, a going concern.

But in calling others back to the liberal project, you may ask, what is it that I’m holding up as the ideal? And is it possible to define that ideal in a way that invites humility, conversation, and discovery, rather than tests of ideological purity?

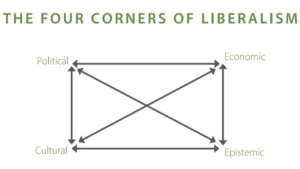

In the many conversations I’ve had on the subject, I have found it helpful to begin by describing what I call the “Four Corners of Liberalism”: political, economic, epistemic, and cultural liberalism.

Political liberalism is the political philosophy that underlies the Declaration of Independence and Bill of Rights. Institutional “rules of the game” that protect individual rights are the best way we know of for ensuring that all people are treated equally before the law. Liberal political arrangements constrain government power and keep authoritarian populist impulses in check. In the American context, civics education, stories of the country’s founding, and national celebrations have rendered political liberalism the most widely recognized dimension of the liberal project.

Less well understood but equally important is economic liberalism. As economic historian Deirdre McCloskey observes, economic liberalism is the mother of the 3,000% increase in material abundance the world has experienced over the last 250 years. When people have the elbow room they need to innovate, produce, and exchange, they tap a creative force that generates that abundance. To be sure, liberals disagree with one another about what constitutes the right mix of economic freedom and government regulation. But liberals broadly agree that market society is an essential piece of the good society.

The third corner of liberalism—what I call epistemic liberalism—represents the formal rules and informal norms that invite the open exchange of ideas and sustain the collaborative effort to seek truth. Freedom of speech is an essential starting point. But epistemic liberalism goes further, carrying with it expectations of honesty and an obligation to exercise critical reason. It demands that we abide by recognized standards of evidence and subject our arguments to the scrutiny of others. When people insist that universities adhere to the principle of academic freedom, that college campuses promote the open and fearless exchange of ideas, they are giving voice to this corner of the liberal project.

At the fourth corner of the liberal project is cultural liberalism. The baseline of cultural liberalism is the recognition that each of us is the other’s dignified equal. From that basic starting point of respect comes toleration. So long as no one else’s rights are violated, we should tolerate the choices of others. From toleration, pluralism often springs. When we are tolerant of one another, more often than not, we learn that we can coexist—become friends, even—with people who have led lives very different from our own.

Liberalism works as a system. Each of the four corners has a relationship to each of the others. (Hence the double-headed arrows in the figure above.) Cultural liberalism, for example, depends on the freedom of association found within political liberalism. Epistemic and economic liberalism work together to promote innovation and scientific discovery. Liberal cultural norms reduce the costs of enforcing the rules that bring about political and economic coordination, and so on.

The arrows also signify tensions across the four corners. The dynamism that economic, epistemic, and cultural openness creates, for example, can be socially disruptive. That disruption can make it tempting to use the levers of government control to “restore order,” overriding the civil liberties associated with political liberalism. The intellectual, civic, and political work required to address those tensions is the work we sign up for when we say that we want to be part of advancing the liberal project.

And we’re better off when we do that work with other liberal thinkers, whether they be left-of-center liberals, classical liberals, or small-government conservative liberals; or whether they be social scientists, philosophers, or cultural critics. No single discipline has a lock on the liberal project. My own discipline of economics, for example, has a lot to say about liberalism, but if we only hang out at the upper righthand corner, we miss a great deal of the action.

The “Four Corners” mental model is useful not because it answers all the questions or resolves all the tensions the liberal project presents, nor because it provides an ideological purity test. In fact, deploying it in such a fashion would be to miss the point entirely. The model is useful because it invites inquiry around and across each of the four corners. It encourages a diverse community of liberal thinkers to see one another, even as they disagree, as fellow liberals. And it puts those thinkers in close enough proximity to one another to identify common ground and, together, make swifter progress toward the good society.